Andrew Grottkau, McMurtry 2019

As I stood in the Los Angeles airport terminal waiting to board my flight to Hawaii, I should have been excited. I was about to embark on what I expected to be the trip of a lifetime: a two-week journey split between Maui and the Big Island.

But as I looked out over the mob of people lined up to board the plane, I felt only worry. My goal when I planned this trip with my girlfriend, Jenn, was to experience Hawaii in an atypical way. We wanted to avoid the resorts, the upscale sea bars, the tourist traps and, perhaps most importantly, the tourists themselves.

In that airport crowd, I saw exactly what I was hoping not to see: the honeymooners wearing shirts that read ‘Just Maui-ed’ on the back, the older couple carrying designer luggage and already in line for first class, and the family wearing matching neon t-shirts with ‘Miller Family Vacation 2019’ emblazoned on the back. What if I was heading for two weeks surrounded by these people?

Tourists are unavoidable in Hawaii. About 217,000 jobs in the state depended on tourism as of early 2019, according to an article from Travel Pulse. Tourists spent $17.82 billion in Hawaii in 2018, which set an all-time record.

My fear, then, was justifiable. Jenn and I were, of course, tourists ourselves. But we had planned the trip carefully, making sure we would only camp and stay in Airbnbs instead of getting stuck in hotels in the towns designed for tourists. There would be no avoiding the mobs of visitors who flocked to the islands to relax in luxury. At least, that’s what I believed for the duration of the six-hour flight to Maui’s Kahului International Airport. But over the next two weeks, I would discover that it is not only possible, but easy to enjoy and preserve Hawaii’s natural beauty despite the large tourism industry.

Perhaps the most spectacular thing about Hawaii is the contrast between its violent past and its idyllic present.

The Hawaiian Islands are part of the Hawaiian-Emperor Seamount Chain, an enormous, mostly-underwater mountain range that begins in the northern Pacific Ocean near Alaska. Each island is actually a volcano, or multiple volcanoes, which began at the sea floor and grew over millions of years as the lava they erupted hardened into rock and added to their height. The mountain range stretches from the northwest to the southeast due to the motion of the Earth’s tectonic plates. While the hotspot that causes the volcanic eruptions has remained stationary, the slow drift of the Pacific Plate to the northwest has caused new volcanoes to form, each new one southeast of the older ones.

The Hawaiian Islands are simply the newest volcanoes in the chain—the older ones have eroded beneath the sea since they went extinct. There are currently only three active volcanoes in the chain: Kilauea, the most active volcano in the world (last eruption: 1983 to 2018); Mauna Loa, the largest active volcano in the world (last eruption: 1984); and Loihi, which is currently thousands of feet below the ocean and is not expected to breach the surface for another 10,000 to 100,000 years (last eruption: 1996). Mauna Loa and Kilauea are both part of the Big Island, while Loihi is about 25 miles southeast of the Big Island.

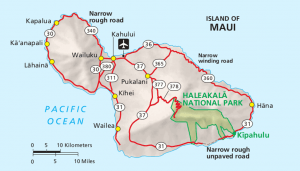

Maui, the first stop of our trip, was created by two volcanoes: Mauna Kahalawai, an extinct volcano that forms the West Maui Mountains; and Haleakala, a dormant volcano that makes up the eastern part of the island. Mauna Kahalawai has greatly eroded since its last eruption over 320,000 years ago and stands just 5,788 feet at its highest point. Haleakala, however, reaches a peak at 10,023 feet and last erupted between the years 1400 and 1700—extremely recently in geologic terms.

This means that regardless of where you are on the island, you’re on a volcano. And these volcanoes support all sorts of natural wonders. In the northwest, there are forested mountains, surrounded by shrubland and flanked by jagged, black cliffs. The southwest contains beautiful beaches with coral reefs just offshore. The east side of the island features the alien-like environment of the Haleakala summit, rainforests and waterfalls along the Hana highway, and even lava tubes from old lava flows.

The abundance of possible attractions was evident almost as soon as we arrived. We set out the first day to drive to the west side of Maui to snorkel in a marine life preserve. Instead of following the GPS, we elected to go the long way, following the highway on the north side of the island instead of the south side. The road, which often went down to one lane to support two-way traffic, ran along the shore, giving wonderful views of the ocean and the island’s black cliffs.

The first stop we made was at a trail leading to the Olivine Pools. The pools were formed by volcanic basalt, a black rock created by cooling lava. They are so named because of the presence of the green mineral olivine in the rocks, which makes the dark, jagged shore glow slightly green in the sunlight. While this sharp, black stone served as a reminder of the island’s violent volcanic past, it has become another mark of the island’s beauty. The dark cliffs stand tall against crashing blue waves, and the pools that remain during the low tide support some of the tropical fish that live in the offshore coral reefs.

The pools were a wonderful example of something we would come to learn about Hawaii. The tourism industry we assumed would dominate the state is in fact limited to certain functions, at least on Maui and the Big Island. Most of the attractions we wanted to experience, like the Olivine Pools, were free. The money tourists spend in the state is concentrated at the resort hotels, the restaurants and the guided tours offered to tourists who do not wish to explore the island on their own. Thanks to the budget I kept throughout the trip (Don’t make fun of me, travel is expensive—more on that later), I know that we spent only $115 on attractions during the entire trip: $50 on a Tri-Park National Park Services pass, $38 on surfboard rentals, $25 to explore a lava tube and $2 to hike to a waterfall. We never even had to pay to park at a beach. For this reason, if your main goal is to see the natural wonders of Hawaii, it is extremely easy to forget that you are on one of the most popular tourist destinations on the planet.

By the end of the day, we had done two hikes along the shore, stopped by a local art gallery, and snorkeled over a coral reef alongside tropical fish and a green sea turtle, all without spending a penny on anything but food and gas.

* * *

The cheap cost of attractions meant that we could spend our money elsewhere. But of course, since we were college students (I guess I’m a graduate now), we did not. We knew from our research when we were looking for housing accommodations that Maui is an expensive place to stay. Nearly all Airbnbs were over $100 per night, not including cleaning fees. Naturally, we wanted to save money. So we decided to camp for five of the eight nights on Maui.

When I described my plans for my trip to my family, they didn’t seem overly concerned that I was heading thousands of miles away and planning my own trip for the first time. They only seemed worried about the camping. Jenn and I had prepared carefully and stuffed a giant duffel bag with everything we could imagine needing, from the tent and sleeping bags to headlamps and a solar phone charger.

After our day of hiking and snorkeling on West Maui, we settled in for our first night of camping at a luxury campsite called Camp Olowalu. The campsite was located along the shore and featured bathrooms with flush toilets and showers—luxuries we would not experience again for the next five days. We set up our bright orange Marmot tent at our designated plot and went to sleep around 8:30 p.m., not long after sundown.

Our plan for the next day was to drive up Haleakala, the 10,023 foot volcano on Maui’s east side. There is a free campsite, Hosmer Grove Campground, located at 7,000 feet just inside the national park. We knew the campsite was first-come, first-serve, so we woke up at 5:00 a.m. to drive to the site as early as possible.

When we arrived, there were at most six tents set up in a space that could easily accommodate 50. Tourists, as we would continue to discover, seldom venture to the most beautiful parts of Hawaii.

And Haleakala was definitely one of the most beautiful parts of Hawaii. After setting up our tent, we drove up to the summit and saw the stunning view of the summit crater. The “crater”—which was actually formed by erosion, not a volcanic explosion—is full of cinder cones from past eruptions. The visitor center gives the best view of the miles long valley, which contains a rainbow of color: The red and black of the volcanic rocks, the pale blue sky, the green of the foliage on the cliffs, and the white of the clouds below combined to form a spectacular, view.

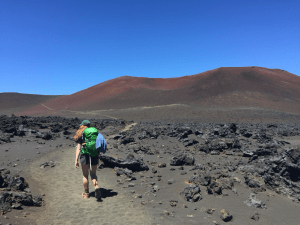

A hike down into the crater gave us an even closer look at the wonder of the volcano. Descending about 2,500 feet into the crater on a trail called Sliding Sands, we encountered an alien landscape. Red and black rocks strewn over the ground made it seem as though we were walking on the surface of Mars. Strange, spiny plants called Haleakala Silver Swords, which only grow on Haleakala between 7,000 and 10,000 feet elevation, looked like something out of a science fiction comic. The eeriest, but most rewarding moment came when we stopped for a sip of water and realized that we could hear absolutely nothing. No people, no wind, no birds, no swaying trees. We were completely alone on the island of Maui.

After an exhausting climb back up the sandy trails, having traveled over 12 miles in all, we arrived back at the summit just in time for sunset. Sunrise and sunset on Haleakala are popular occasions, and for good reason. From the perspective of the visitor center, the sun sets over the rest of the island of Maui and rises over the Haleakala crater. Jenn and I decided to watch both from the summit of Haleakala.

The dual experience of watching the island plunge into darkness as the sun descended and seeing first the valley, then the rest of the island light up the next morning as the sun rose was completely worth the 2:45 a.m. alarm we had to set in our tent to drive to the summit. 2:45 was too early—we arrived to the summit about an hour and half before sunrise—but it allowed us to look at the stars from the summit until the sun rose. The sky is so clear from the summit of Haleakala that we could make out the Milky Way as we laid in the cold morning air. Yet again, other than a couple we befriended while looking for the best spot to watch the sunrise, we were totally alone to bask in Hawaii’s landscapes.

* * *

Camping, as it turned out, was hardly a hassle. After a second night spent on Haleakala so we could watch the sunrise again, we drove to the other side of Haleakala National Park, an area called the Kipahulu region. The drive to the park was treacherous—despite what the map may look like on your phone, don’t drive on the south side of East Maui unless you have four wheel drive, are comfortable with nearly falling off cliffs, and enjoy almost being run into by free-range cows; use the Road to Hana instead! Despite the large concentration of tourists due to Memorial Day Weekend, we found an isolated campsite under two large trees right on the shore.

The site was near enough to Hana that we drove into the town to get some food and supplies. Hana was almost completely isolated from tourists and much of Maui as well until the Hana Highway was completed in 1926. Even now, the famous Road to Hana is intimidating enough to keep some people away. The 52-mile road, according to locals, has 620 curves, 59 bridges, and in many areas is only wide enough for one car to pass at a time. The town only has a population of about 1,200 people, but as the Road to Hana has become more popular, tourists have morphed it. A resort hotel opened in 1946, and there are currently food truck parks and a couple upscale restaurants to cater to the brave adventurers who navigate the highway.

The attractions of the Hana area are the rainforests and beaches surrounding it. It is home to a red sand beach and a black sand beach, and there are plenty of trails up into the foothills of Haleakala. One trail we hiked snaked through a bamboo forest and led to a towering waterfall at the top.

Most of the tourism in Hana focuses on the road instead of the town itself. When we finally camped for the last of our five nights, we drove the Hana Highway back toward Kahului and did some of the more typical touristy activities. This was the only time in the entire trip that we noticed how the tourism industry had taken advantage of Hawaii’s natural wonders. We stopped at Maui’s largest lava tube, a deep black cave created by an ancient lava flow, and paid $25 to explore it. We bought banana bread, smoothies and pork sandwiches for lunch—a must along the Road to Hana. We fought for a parking spot to swim underneath a waterfall on the side of the road. All of these activities were extremely fun, but for the first time, I finally felt like a tourist in Hawaii. I took solace in knowing it took half of the trip to get to that point.

We spent our last day in Maui surfing on the west side of the island near Kihei, a resort town. The next morning, we awoke in our Airbnb to the sound of our alarm and some screaming roosters—there are quite a few on Maui—and jetted off to the Big Island.

The first thing we saw on our flight’s approach to the Kona Airport on the Big Island was a lava flow. A small car was driving through what appeared to be an endless field of black rock, unlike anything we saw on Maui. Indeed, Kona was extremely unlike Maui. Nearly everywhere on Maui felt either urban or rural, with little in between. Driving through Kona, though, was like driving through a large suburb like Cypress, Texas—if Cypress had spectacular views of the ocean and an occasional lava flow, that is.

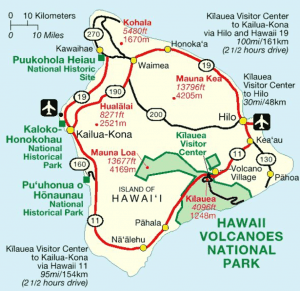

The most obvious difference between the Big Island and Maui was, predictably, the size. We drove an hour and a half from Kona down the west coast to reach the southernmost point of the island, where we hiked to a green sand beach. It took us over two hours the next day to drive to Hawaii Volcanoes National Park in the southeast.

We made a major stop along the cross-island journey. The highway that cuts east-to-west runs right between the two largest mountains on the island: Mauna Loa, the largest by mass, and Mauna Kea, the largest by height. While there is no way to reach the summit of Mauna Loa by car—it’s an active volcano, and an eruption would surely destroy any road in its path—a turn off the highway leads directly to the Mauna Kea Access Road.

At 13,803 feet, Mauna Kea’s summit is the highest point in the state of Hawaii and, due to Hawaii’s isolation, the tallest point of elevation for nearly 2,500 miles. In part due to this isolation (and also due to its dry climate and stable air), it is also one of the best places on Earth to look at the stars. For this reason, there are 13 powerful telescopes at the summit. Two of the eight telescopes used to take the first images of a black hole are located on Mauna Kea.

The presence of these telescopes, however, is an example of the ways western influence has come in conflict with Hawaii’s natural landscape and history. According to Native Hawaiian tradition, the summit of Mauna Kea is a sacred site. Therefore, the presence of the observatories remains controversial. The construction of a new Thirty Meter Telescope, approved in April 2013, has faced numerous protests, most recently in July 2019.

Even by car, the climb is not easy. A paved road leads to a visitor center at about 9,000 feet elevation, and signs alert drivers to stop at this point. To our surprise, there was no fee to reach the summit—unlike Haleakala, Kilauea and Mauna Loa, Mauna Kea is not located in a National Park. The rangers inside recommend at least a half hour, and ideally more, at the visitor center to reduce the risk of altitude sickness before heading to the summit. Every car driving to the summit must have four-wheel drive due to a steep, unpaved section of the road that runs for nearly five miles after the visitor center.

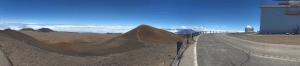

The reward for reaching the top is a spectacular, barren landscape. The dangers of the climb apparently deter a large portion of visitors—when we ascended, there was only one other car at the summit alongside us. The views were somewhat similar to Haleakala, with red and black rocks littering the area and cinder cones popping up here and there. There were two major differences from Haleakala, however: one, the presence of the observatories, and two, that the landscape did not seem to end. The clouds below cut off any view of trees or ocean, and we were left standing alone without a living thing in sight besides the couple in the nearby car.

Both Jenn and I began feeling lightheaded after a climb up a short hill to what seemed to be the highest point on the mountain, so we decided to turn back before any potential altitude sickness kicked in.

Our final stop on the trip was the Hilo side of the Big Island, home to Hawaii Volcanoes National Park. Between 1983 and 2018, Kilauea, the main attraction of the park, was continuously erupting, emitting lava slowly from the Pu’u ‘O’o cone and usually causing little damage to its surroundings. The eruption ended in 2018 when Kilauea’s East Rift Zone roared to life, spurting lava fountains up to 300 feet high and releasing flows that destroyed much of the Leilani Estates, a nearby residential area. It was the most destructive volcanic event in the U.S. since the eruption of Mount Saint Helens in 1980.

Thus, when we were in Hawaii, there was no molten lava anywhere on the island. This did not stop us from extensively exploring Kilauea and the surrounding area. We visited the summit crater, which had expanded greatly during the 2018 eruptions, and numerous other pit craters from past eruptions. We walked atop lava flows from as recent as 1973—one of which had only completely hardened in 1997.

The most jarring experience of the trip came when we visited the 2018 lava flows. The flows had created Hawaii’s newest black sand beach and built nearly 14 square miles of new land, but it had also decimated a residential area, causing about $800 million worth of property damage. Although it had not taken any lives, it was unnerving to see the roofs of homes peeking above the surface of the flow, buried beneath the massive pile of lava. It felt wrong to be sightseeing—like we were taking joy out of the suffering of others. It was a perfect way to end the trip, a reminder of the destructive force amid the natural beauty of the islands.

* * *

Waiting in the airport to board the flight back to the mainland, I thought back to the feelings I had standing in the Los Angeles Airport. The same annoying tourists I feared I would encounter at every turn were back, looking more tired and less hopeful than they had been on the front end of the trip.

An angry 50-year-old man was frantically searching for his hat, which he alleged the TSA agents must have confiscated without telling him. A young woman in dark sunglasses—which was notable given it was 9:30 p.m.—complained to her husband that boarding should’ve started at least five minutes ago. I thought about lucky we were that these people avoided the most beautiful parts of the islands.

The relatively small percentage of vacationers who explore the lush rainforests, towering volcanoes and roaring waterfalls never made the island’s tourism industry feel overbearing. Conversely, standing alone in the Haleakala crater or staying in our own private camping spot on the ocean, it almost felt like we were discovering some kind of unknown paradise. This was of course not the case—not even close—but the fact that it was possible to feel this way speaks to the tendency of most tourists to stay in private resorts and protected beaches.

There is some value to relaxation, of course. But if you’re going to travel thousands of miles to the middle of the Pacific Ocean, it’s worth going out of your way to see some of the most beautiful landscapes on Earth.