Iceland and the Modern Adventure

Drew Keller | 2018 Schumann Brothers Grant for Travel Journalism

I’ve always loved road trips. My parents favored them for our vacations, and as a result many of my school breaks used to be spent in the car. During the many hours and thousands of driving miles these trips entailed, I used to imagine I was traveling through some imaginary place, or on an expedition into an unexplored and perhaps slightly dangerous land. Something about the North as an idea always fascinated me in particular; driving north through Banff National Park in Canada or towards Denali in Alaska, I recall imagining heading into the depths of the Arctic itself.

I was excited, then, as I peered out the plane window at the promisingly bleak-looking Icelandic heath (above) while descending toward Reykjavík International Airport this summer, ready to embark on a week-long automotive exploration of the country. Iceland offered an opportunity for me to dream those childhood dreams writ large.

There must be others like me, given the rapidly growing popularity of Iceland as a travel destination — because that’s what the country really presents, a grown-up-sized playground to live out a fantasy of wildness, adventure, expedition — all at grown-up-sized prices, of course.

We live in an age where the cult of oneness-with- nature grows greater by the day. We value our certified-outdoorsy tans; we pay to go on device- free nature retreats; in Dallas, I live beside a popular all-natural juice store (“Raw! Organic! Real! $1/oz!”). Maybe we’re turning away from our world’s excessive suburbanization and ubiquitous technologification by seeking out nature. And maybe there’s a tension between our safe, controlled lives in civilization and the pull of our wild history as humans — for most of humanity’s existence we’ve been in a state of struggle with nature, as reflected in the widespread popularity of survival literature and TV.

Wilderness, after all, is a human construct as well — it’s only defined in opposition to human civilization, and often is far more human- impacted than we believe. Scientists believe the “pristine” wilds of North America used to feature giant beavers, rhinoceros and lion species, and 8-foot-tall “terror birds” prior to the extinction- inducing arrival of prehistoric humans. The Amazon rainforest’s “untouched” biodiversity may have been shaped by millennia of Native American impact. Even Iceland’s great expanses are artificial in some sense; before human settlement, much of the island was forested, but Vikings cut down nearly all the

But we don’t worry about that. To us, wilderness is untouched and eternal. How could a 10-year- old not watch Survivor and read his adventure literature — Hatchet and My Side of the Mountain in school! — without feeling a desire to venture off into the outdoors? How could a 22-year-old not still be influenced by those internalized childhood stories in what he wants, or what he thinks he wants (if there’s a difference)?

So clearly, there’s a worldwide appetite for nature, and more than nature, for wildness, adventure, the feeling of exploration. The downside, of course, is that for most people the “true” version of these things — to the extent it exists, anymore — comes with unpleasant side effects. Let’s define a more real adventure as where, when danger or plain inconvenience strikes, money can’t help you. This sort of adventure is becoming rarer and rarer.

People want the experience of adventure without risk, danger, discomfort, disconnection, the lack of a morning coffee and lunchtime WiFi and a place to sleep after dinner if it rains a bit too hard for tents to be comfortable. People want adventure, but with a first-world hospital within a quick helicopter ride in case, you know, you slip and tweak your ankle or something.

In this regard, Iceland is a paradise, and its booming popularity makes perfect sense. It offers the ultimate 4D adventure experience, complete with stunning panoramas ten kilometers out of Reykjavík to make you feel you’re in the middle of nowhere, interactive hot springs, enough cold and wet weather to boast about your toughness to your friends back home, open roads that give you the freedom to explore your own route (provided that route follows the single paved loop road around the island), a suitably almost-but-not-quite-Arctic-Circle latitude, no pesky dangerous animals, and a narrative of adventure stretching back to those early Viking (Viking!) settlers.

Let’s talk about those settlers for a minute, sarcasm-free. They deserve it, for they epitomize this human ideal of adventure in one of the purest forms ever expressed. Long before the advent of modern lighting or heating, these people came to a cold, empty land that must have seemed like the edge of the world to eke out a marginal existence, mostly through pastoral agriculture and coastal fishing/ gathering. Forget seasonal affective disorder – from November to mid-February, Iceland offers less than 8 hours of daylight. Yet early Icelandic society persisted, even leaving a copious literary legacy (recommended Iceland travel tip: buy an English translation of the Sagas of the Icelanders, featuring narratives such as that of a protagonist who stabs his host for not providing him with beer).

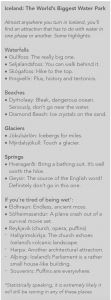

Despite its rich history, culture is not the reason to visit Iceland — not like it is for, say, Spain or France. Sure, there’s the kitschy Viking Museum, but to me the closest I felt to Iceland’s past was at the Hallgrímskirkja in Reykjavík (left), an imposing Protestant church whose simple, unadorned shapes and decorations reflect the bleak, sacred emptiness of the country. Even at Þingvellir, the crown jewel of the Golden Circle tourist route and the location of Iceland’s historic Althings, there’s not much remaining in the way of human culture — the main attraction there is a waterfall and tectonic rift (next page — see two tectonic plates at once! as well as historic execution sites: Gálgaklettur, “gallows rock,” Gálgaeyri, “scaffold beach,” Brennugjá, “burning gap,” and Drekkingarhylur, “drowning pool”).

This isn’t to say that modern Iceland and Icelanders have no culture or history. Of course they do; anywhere does. It’s just harder to find physical places that reflect this in this tourism- soaked destination. With regard to the people, summer travel in Iceland feels surprisingly like being in a cosmopolitan New York or London in terms of the diversity of origins — more specifically, perhaps like walking around an REI in New York, since tourists tend to be of the outdoorsy-chic type (what’s the British equivalent of REI? I have no idea). “We just wanted to be out in the wild for a change,” my seat-neighbor on the flight from San Francisco explained to me. She and her “Not all those who wander are lost”-shirt-wearing fiance had bought a flight out on an impulse a few weeks earlier.

Last year, Iceland saw nearly 7 times as many tourists as it has residents. The fact that these tourists overwhelmingly visit in the summer means that the majority of people you’ll meet in Iceland, wherever you go, will be tourists. From North Americans to Western Europeans to Russians, Chinese and Indians, Iceland in tourist season is surprisingly multicultural for a country whose resident population is 93% Icelandic ethnicity.

People don’t come to Iceland for the intercultural exchange either, though, notwithstanding Reykjavík’s allegedly “popping” through-the-midnight-sun weekend nightlife (warning: this hyped-up phenomenon, of whose existence I am dubious, seems to be a weekends-only event; on a Tuesday night, for example, Reykjavík’s streets and bars were largely empty by midnight or 1 am). What unites all these (sub)Arctic travelers is the pursuit of Iceland’s nature, the path to that hallowed story of adventure.

And Iceland does have copious natural beauty. It shares that quality of other wide-open landscapes closer to home — the deserts of the American west, the tundra of Alaska, the prairies of the Great Plains — the ability to make you feel small, to confront you with scales of distance an order of magnitude beyond what your brain is capable of comprehending. The empty space, the arrow- straight roads, the omnipresent water are meditative. It’s an almost- paradox: a therapeutic desolation.

Why therapeutic? We could turn to religious history for one answer. The original settlers of Iceland practiced what we call paganism: the polytheistic north Germanic variation of the historic Indo-European religion. Pagan practices were largely stamped out as Christianity became established in subsequent centuries, though recently a reconstructed neopaganism has emerged, with a temple currently under construction in Reykjavík. Of course, some pagan traditions persisted despite the adoption of Christianity (famously including “elf” folklore), and it’s hard to not still perceive some philosophical influence on how modern Icelanders see the world.

This complex heritage — Christian influence atop a pagan substrate — is shared across much of the Western world. There’s a line of argument that pagan ideals still infuse much of how we conceive the world around us, perhaps increasingly so as Christianity recedes in our day- to-day lives. At the core of the “pagan” worldview is that divinity is within the material world rather than outside it; meaning comes from fusion with the world around us, not separation. I can’t help but wonder whether this is what many of Iceland’s travelers are seeking: a harmony and communion with nature that lets them feel part of something greater. Or maybe it’s something even deeper: simply a human instinct, an inherited feeling that these obviously-natural settings are where we are “supposed” to be.

So, hypothesizing aside, what is it actually like to travel around Iceland? Well — it’s expansive. A car is a must – be ready for slow speeds (though the kilometer-based speedometer makes you feel speedy when you see “130”) and lots of passing. English is ubiquitous. Gas stations famously feature Icelandic hot dogs, essentially the cheapest food you can buy at “only” ~$5 each. They’re also a great place to socialize with your fellow roadtrippers. In Hella, I chatted with a three-car company carrying an extended Indian family finishing a four-day circumnavigation of the island; in Vík, with an Australian couple lamenting Iceland’s cold, having just come from South America (!).

Well-amenity’d campsites are other ideal spots for people-meeting and -watching. In a communal kitchen at Skaftárhreppur, I watched a middle-aged Austrian woman carefully measure and grind her marijuana before returning to a large cabin-tent. After a few nights of camping in perpetual mist, though, it’s hard not to give in to the temptation of a warm hostel by a waterfall (below).

Most of the sightseers I met had well-scheduled itineraries for their journeys around the country, slightly offending my sensibilities: A road trip with an itinerary isn’t an oxymoron, but it should be! An itinerary subverts the total freedom a road trip is supposed to stand for — that idea of freedom that helps make road trips an American ideal, leaving aside the ways cars trap us financially, environmentally, in urban design.

“Adventure,” “wild,” “nature” — asking those you encounter the motivations of their trip, you’ll hear these same words repeated, and say them yourself. You’ll join hundreds hiking two miles across an empty plain to a plane’s wreckage, an apocalyptic setting where it’s easy to imagine shots of a lone survivor crawling out of crash and limping across desolate sands, while the camera pans out and music swells. The reality, again, is a bit less dramatic — all crew members parachuted to safety.

In general, no one seems too disappointed that Iceland’s adventures are on a rather smaller scale than the grand ideas my campsite-mates and I are chasing — maybe because they seem taxing all the same.

Rather than eating seals like Shackleton, we’re struggling to heat ramen on a rickety camping store in the rain. Rather than being mauled by a grizzly a la Leonardo DiCaprio, our car’s windshield is getting lacerated by a pebble thrown up by the truck in front of us (this little rock shattered the rain-detecting photodiode in the windshield, costing me $2000 upon the return of the rental. Luckily, my travel insurance ultimately covered the incident).

That’s probably because most of us find what we’re really looking for in Iceland: a way to reconcile our adventurous dreams, created from stories, with our customs of lifestyle and experience. After all, if not from instincts, from inherited ideas, from the media we consume, where else could our goals and motivations come from? (Just because the aspiring doctor’s aspiration originates with Grey’s Anatomy doesn’t delegitimize it.) Iceland demonstrates the degree to which people from all over hunger for wildness — and, like a Icelandic lamb stew after a day in the rain, it offers a kind of satiation.

Thank you to the Schumann Brothers and Rice University Student Media for making this trip possible.